“While some might consider it a dubious distinction, being the best at retrieving the dead, to Nico, it was a sacred avocation. Curiously, the one thing that actually made him feel alive.”

The Lincoln County Sheriff’s volunteer dive team had set up a line of jackstays perpendicular to the Alsea Bay Bridge. Lingering evidence of their earlier, unsuccessful search for the body of 7-year-old Misty Leander. The blaze orange buoys now pulled in the direction of the outgoing current. This ebb tide was the first thing Nico noticed arriving at the scene. It triggered a flash of discomfort. He knew it could bode either way for the recovery efforts. Lower water levels in the bay might expose the little girl's body. But the force of its retreat could just as quickly sweep her over the Alsea Bay bar and into the vast, gray expanse of the Pacific, where she would be lost forever.

Death without a body was a gaping void nearly impossible to fill for those left behind. Nico was forced to swallow this bitter lesson at just ten years old when his father failed to return after just one of thousands of freedives he’d made over a lifetime harvesting sponges off the coast of Tarpon Springs. It was a Sunday distant in years and miles, but also so much like this one. The arrival of an unwelcome grief, a new inviolable reality presenting itself as a family’s new and dreaded defining moment. But Nico would not let the sea take Misty Leander’s body, as it had already taken her life. He dismounted his truck, walked to the shoreline, placed the palm of his right hand on the gray-green water of the bay, and closed his eyes. She was an accident, he explained, a miscalculation unlike his father, who was fair harvest after daring the sea one too many times.

“Who’s that?” Timothy Leander asked, looking at the bearded, long-haired stranger and talking to himself at the water’s edge. He wiped away the pudding of snot and tears from his face with the already crusted back of his sweatshirt sleeves and stood up from one of the folding chairs set up for the family inside the Incident Command Tent.

It had been erected on the north bank of the bay, closest to what the searchers identified as the LPS or Last Place Seen. Ray Falk, the senior member of the Sheriff’s volunteer divers, looked in the direction Leander was pointing. Falk, with the others, had searched the waters all morning and early afternoon but was now sipping coffee to ward off the body chill of those long, fruitless dives and had stripped his red public safety diver dry suit to his waist.

He squinted at the figure as he came closer, smiled, and reached out his hand in recognition.

“Hey, Nic,” he said. When Nico looked at him uncertainly, he said, “Ray Falk. Worked with you for a week last year at Beaver Lake. Recovery of that kayaker?”

Nico held his gaze, Falk’s face coming back to him slowly, vaguely.

“Right, Ray.” He said, taking the man’s hand but looking over to Leander.

“You, the dad?” He asked.

Leander nodded.

Nico had been debriefed by phone on the drive down from Garibaldi but still wanted to talk to Misty’s father and mother and sift whatever critical details might have been missed in the interviews conducted immediately after the event. The heated mixture of panic, fear, and grief muddied their memory, making it as resistant and opaque as the bay waters before them.

Timothy Leander did not want to tell the tale again. Nico sat him back down and took a knee before him in a penitent’s pose while Leander rocked into himself, hunched over a starter paunch sheathed in an oversized green Dickie’s t-shirt and unzipped gray hoodie. Nico could hear the rush of the outgoing current. He placed a consoling hand on his knee but squeezed his fingers into his patella to bring the grieving father back into focus.

“Timothy,” Nico whispered. Leander sniffed once and looked up, hair sheepdogging over his eyes. “Misty is out there,” he gestured. He had the young man’s attention again. “I can get her back. Then you and your wife can say a proper goodbye. But you have to help me.”

Nico glanced back over his shoulder. The gray harbor seals were already claiming patches of sand emerging from the receding water. Time was slipping away.

Leander looked to where his wife sat, comforted in the arms of a female sheriff’s deputy, her hair wet underneath the hood of her XXL tan Carhart jacket and a gray blanket draped over her shoulders. He saw that it was up to him. He sat upright and drew in a breath. Told Nico how Misty had begged him to launch one of the crab pots over the aluminum rails of the rented, 15-foot Smoker Craft outboard. Said he gave in to her, like he always did, impossible to say ‘no’ to her endless ‘Please Daddy, pleases.’

Leander exhaled as if it were his last breath.

“I helped her lift the trap to the edge so she could nudge it over and into the water. But you know what was weird?” He asked. Nico shook his head.

“I remember almost being, like, hypnotized looking at the bait.”

“The bait?” Nico asked.

“Yeah, the frozen chicken in the center of the trap. I mean, I’m the one who put it in there. Marian don’t like to touch it,” he looked over at his wife. “And Misty sure don’t. She called it ‘icky,’” he smiled, recalling. “But it just held me still for a few seconds. That bumpy white skin of the frozen chicken legs I put in there. Then Misty surprised me. She pushed the trap into the water before I was ready,” his voice cracked. “Before I told her it was okay. That’s just the way she was. She was always running ahead. She didn’t have no patience.” Leander shrugged. “But she’s just seven. Nobody got no patience at seven.” Leander wiped at his eyes and looked off over the bay. “The world’s a wonder at that age.”

“It is,” Nico agreed but considered another ‘wonder.’ Why the Leanders hadn’t thought to put a personal flotation vest on their daughter—or themselves, but now wasn’t a time for blame. They would have years to think about what they might’ve done or hadn’t done right in the aching absence of their child. “What happened then,” Nico prompted.

“She was leaning too far over the edge of the boat,” Leander said, “wanted to see the splash when the cage hit the water. But when it slid over the bow, the net snagged the sleeve of her sweatshirt.” He paused, fortifying a crack in his voice. “Drug her right under. Bay swallowed her up, just a flash of pink … then nothing.”

“What about the line securing the trap,” Nico asked.

Leander nodded. “Right away, I pulled up on it,” he pantomimed the action.“But the knot came loose or something. Nothing on the other end. Trap was gone, Misty with it.” He wiped his eyes. He seemed ready to slip back into himself, a useless miasma of second-guessing and self-reproach, when Nico gripped his knee again and pressed him for more.

“And after that?” Nico asked.

Leander spoke quietly, “Marian stood up in the boat,” and nodded toward his wife. “She was trying to reach Misty but lost her balance and fell backward.” He shut his eyes and labored to remember the order of the events. “She was splashing around, reaching out to me. She’s not a swimmer.”

Again, lifejackets, Nico thought but tried to keep the judgment off his face.

“Well, not a good one,” Leander continued. “And that water’s cold. I could see in her eyes she was panicking, but I was also looking down at the bubbles. That spot where my girl disappeared.” He choked back a sob. “I didn’t know which direction to reach, but Marian looked like she was about to go under.” He took a deep breath. “So, I went for her first. Pulled her arms onto the side of the boat. By the time I was able to get her back in I lost where Misty gone in—and I couldn’t see no more bubbles.” Brought his hands to his face.

“After the trap line came undone,” Nico said, drilling down. “Which way did the trap buoy drift? Toward the bridge or away from it?” Leander looked puzzled and took a few beats before answering.

“Away from it … I think. But a lot was goin’ on.”

“If you want your girl back,” Nico mirrored Leander’s words, “you have to be certain. Toward the bridge or away from it? And after, was it moving toward shore or the bar?”

Leander looked like he might break into a thousand pieces. Then Marian Leander spoke up.

“It was drifting toward the bridge and away from the bar,” she said with no hesitation.

“How do you know that?” Nico demanded, refocusing from Timothy to her.

Marian Leander pulled away from the deputy and pushed the hood back from her face. Strands of wet blond stuck to her forehead. Her eyes streaked black where tears and the bay water washed away her eyeliner.

“I know because the front of the boat was pointed at the spit. The water was slow then but still running back upriver. Level getting higher then, not lower.” Nico stood up and looked at his watch. He nodded his thanks, but she called after him before he could turn away.

“Mister.” He stopped and looked at her. “My baby girl hates to be alone in the dark.”

“Me too,” Nico said, nodded.

“Don’t come back without her.”

“I wouldn’t. Won’t.” He said.

“Promise?” She asked, stepping forward

He lifted his little finger, curled it into a pinkie swear -- and she returned it.

“Tell me one thing before I go.”

“What’s that,” Marian Leander asked.

“Misty’s favorite song? The thing she’s always singing and dancing.”

This time, Timothy spoke up. “Frozen,” he said. She loves the Disney movies.”

“But what song?

Timothy looked at his wife. “Let it Go,” he said. She nodded to confirm.

Nico searched his phone. “Got it,” he said. He hit play and held it to his ear while he walked to retrieve his gear in the back of his pickup.

Once out of earshot, Timothy Leander turned to Ray Falk. “You all sure he’s the right guy for this? When we was talking,” he paused, “I could smell the whiskey on him.”

~ ~ ~

Nico looked over the water, considered the information the Leanders had given him, and calculated two key scientific determinants of his peculiar profession: the body descent graph, an approximation based on time and temperature of whether a body will most likely be found on the bottom or at the water’s surface based on its retention of internal gasses. The body movement path, based on tides, current, and flow of where a body will likely travel through the water from the Last Point Seen or LPS. Nico’s ability to predict these two things with uncanny accuracy was the reason he’d been asked to come here in the first place. Nico Papadopoulos, aka The Grim Deeper, had more than a hundred body recoveries in his 20-year career as an Oregon State Police Search and Recovery Diver. He was the one called when others failed to find someone lost or disposed of in the water.

While some might consider it a dubious distinction, being the best at retrieving the dead, to Nico, it was a sacred avocation. Curiously, the one thing that actually made him feel alive.

His hands stretched out the silicone neck seal of his drysuit, so it didn’t rip when he pushed his head through. While the October air temperatures were still mild, the water hovered at a bracing 50 degrees, according to the averages registered by the volunteer divers. He'd be a little cool with only a 100-gram Thinsulate undergarment for insulation, but he preferred that. Better to allow him to feel the thermal signature. He pulled the zipper across his chest and ensured it locked in place at the end of its draw. He paused for a moment to admire the surroundings. How brutally beautiful this place was. While the town of Waldport barely made it onto the state map, its Alsea Bay attracted fishermen and crabbers from across Oregon. A late afternoon mist clung to the needles of their uppermost branches of the Douglas Fir, Ponderosa, and Sugar Pine that edged the shoreline. A postcard-ready, art deco-style bridge joined the Bay’s north and south banks with thick stone footings and a high-looped arch, supported and cinched by dozens of braided steel cables. The city’s website claimed that during the coldest and wettest months of winter, the winds blowing through them created haunting music. Nico hoped to hear it one day but as just another traveler driving up the coast, not as a diviner of death, plumbing the bottom of the bay for the body of a child.

He pulled on his 7mm neoprene hood, carefully tucking back his hair and beard to ensure a good seal with his full-face mask. Then he donned his fins, but before entering the water, he completed a radio check and reviewed rope signals with his tender, a cocky young man the others on the volunteer dive team had nicknamed Johnny Bravo. Nico explained to him that one tug on the coil of nylon rope he wore around his waist meant stop. Two tugs, everything was okay. Three tugs let out more slack on the line. Four tugs meant he found her. Any more than that from the diver signaled an emergency of some type, and the tender should pull him back to shore. Likewise, if the tender pulled five times on the rope, the diver should return immediately.

Nico inflated his dry suit and waded in. Floating at the surface, he checked for bubbles that would reveal leaks in his neck and wrist seals or holes in the suit laminate itself. Problems that could turn a recovery diver into an additional victim. When satisfied, he gave the tender an ‘okay” sign and a thumbs down to indicate he was ready to descend. As the glass of his mask broke the tension of the water’s surface, his world turned pale, milky green, and he felt, as he always did at this moment, filled with purpose and an otherworldly calm punctuated only by the sound of his breathing. When he clicked off his radio, Johnny Bravo flinched. He was about to give him five pulls, the tender to diver recall, when Ray Falk, who was supervising the surface operations, stopped him.

“This is how he works,” Falk said. “Doesn’t want anybody in his ear while he’s down there.”

“Why?” Johnny Bravo asked.

Falk hesitated and took a sip of his coffee before answering. “Says he won’t be able to hear them.”

“Hear what?” Johnny Bravo asked, puzzled.

Falk nodded, “When they’re calling to him.”

“That’s fucking crazy,” he answered, but in a voice low enough, the Leanders wouldn’t hear him. “He comes here smelling like the Jack Daniel’s Distillery tour, talks to the water, then turns off his comms so he can hear it answer back?

“You know what’s fucking crazy,” Falk said, growing irritated, “is that guy on the other end of your rope never comes back without them. Not once. So, if you got a problem with that, Johnny, hand me the line and sit in your truck where you’re less likely to piss me off. And maybe you should think about doing a little less talking and a little more listening like Nic out there, and you might learn something, too.”

The rope tender shook him off and kept his eyes on Nico’s bubbles as they tracked along the west end of the bridge, toward the south bank of the bay, weaving back and forth in a slight zig-zag pattern but headed in the direction of the bar and the open ocean.

~ ~ ~

Nico plucked his way along the muddy bottom in near zero visibility, weaving his hands in front of himself like two crossing arc lights, hoping to brush against something that should not be there. Sometimes, he’d catch the silver glint of a Lingcod or a scuttling family of Dungeness crabs in the glare of the 1000 lumens light mounted to his mask. Every few feet, he’d stop finning forward. Spoke into his mask.

“Misty,” he whispered, “Misty.” Gently, he kicked forward. Listened. Repeated in each direction, staying silent amongst the slow tidal drawback and dull clicks of ten-thousand-crab claws. Long ago, Nico learned to de-emphasize visual input in his search and recovery dives. Sight was usually the least helpful sense in his line of work since the muddy lakes, rivers, and bays like this one were saturated with the brown tea of long-decaying organic material or neon algae blooms exploding along the shorelines fueled by the chemicals of agricultural runoff.

During the early days of his search and recovery training, Nico was intrigued by reading about the exploits of a blind salvage diver named Bert Cutting. When a barge dumped a load of 155 cars into the Ohio River in 1951, Cutting, by touch alone, retrieved 146 of them, plus the barge itself. He worked underwater, 6-8 hours a day for 100 days, using a homemade metal shallow water diving helmet with no glass viewing ports and supplied with air by a garden hose and compressor built from a washing machine engine. Old photos depicting Cutting wearing the windowless contraption made it appear like he had caught his head in a stovepipe. But regardless of his humble equipment, Cutting’s superhuman effort saved the company more than $300,000, a veritable fortune for the time, and earned Cutting an entry in Ripley’s Believe it or Not.

Like Cutting and most other salvage and recovery divers, Nico also worked to develop his other senses, sound, and feel primarily. But it took a near-death experience to understand his heightened abilities in each.

After five years working as a police diver, Nico contracted a water-borne bacterial infection following the search for a murder weapon in a stagnant stretch of the Willamette River just south of Portland. While he found the target, a 10-inch Bowie knife with a rusty, serrated spine that had been used to saw the jugular of a meth addict who pissed off his buddy by stealing his last cigarette, the consequences in securing justice for the man were steep. The morning after the dive, Nico woke up with a world-shattering headache that made him want to suck the 115-grain, 9mm Lugar rounds out of his service Glock just to stop the pain. Within hours, he had a temperature of 105 and rising, was projectile vomiting and hallucinating that the ends of his fingers were splintering like string cheese and that his long-lost father was swimming through his apartment picking sponges from the kitchen sink. It took specialists a month to pinpoint the cause and another six months of treatment to bring him back from the brink, including a weekly regimen of blood transfusions and heroic daily doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics to kill whatever it was that had invaded the meninges lining of his brain. When it was finally over, Nico felt like a husk of the man he once was. He’d lost 30 pounds, struggled with concentration and short-term memory, as well as a 15-percent hearing loss in his right ear. He was assigned to desk duty indefinitely.

But Nico wasn’t made for a life lived only above water. The change triggered a black-dog depression that felt impossible to shake. He managed it with an open Lorazepam prescription, handles of Old Forrester, and weekends on the couch doing nothing but drinking and watching classic movies marathons. The Philadelphia Story, his fave, probably seen it a dozen or more times already because where else could you watch Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, and Jimmy Stewart chew up the scenery together with dialogue so sharp it should’ve made their lips bleed? He also enjoyed the myriads of drinking references, poorly aged as they were like Grant’s C.K. Dexter Haven popping off gems like, I thought all writers drank to excess and beat their wives. You know at one time I think I secretly wanted to be a writer.

Or Stewart playing Macaulay Connor defending Hepburn’s character to her ex-husband, Grant’s, C.K. Dexter Haven.

Connor: She's a girl who's generous to a fault.

Haven: To a fault, Mr. Connor. Except to other people's faults. For instance, she never had any understanding...of my deep and gorgeous thirst.

Watching it made Nico feel he wasn’t drinking alone but in splendid, witty company. At least until he blacked out. He repeated the process until Monday morning rolled around and the new work week arrived. But months after the same destructive routine, Nico threatened to quit the force if he wasn’t reinstated full-time to the dive team. His supervisor eventually relented. Told him it was his funeral.

“I died months ago,” Nico cracked then. “Right after you parked me on the desk.”

It took time to get back in shape after so long out of the water, but it was on one of those early post-recovery dives that Nico found that his ordeal had done more than just diminish him. In some strange, inexplicable ways, it had made him better.

During the search for a victim of domestic violence, a 27-year-old mother of three, strangled by her boyfriend and dumped in the Bonneville Dam, Nico grew frustrated when the team’s search patterns failed to locate her. While the others took a lunch break, he grabbed a fresh tank and re-entered the water alone. He tried whispering her name, Pam, and repeated it almost like a mantra. He said it so much his onshore tender asked why he was talking to himself. Nico turned off his comms and continued.

Then, after 20 minutes of calling her, he heard something back, not so much words, but the hum of some kind of echolocation, like that used by bats and dolphins. The tone grew higher in volume and frequency the closer he got to her. After another 30 minutes of searching, with only a third of the air left in his cylinder, his hand brushed the soggy toe of a fleece boot under an accumulation of logs, plastic, and other debris at the base of the dam.

His next touch landed on her calf, covered in denim but the shape beneath it soft and pliable. Next, he touched her hip and breast and felt the snag of her long hair in his gloves. Then, in the formal ritual he always performed when recovering a body, he knelt before her and removed the black PVC bag from the thigh pocket of his dry suit. Reverently, he spread it out from head to toe and unzipped it.

He placed a gloved hand on her body and recited the words he always said, only the name itself changing.

“Thank you, Pam, for helping me find you. This is not where you belong. If you’re ready, I’d like to bring you home.” Then, as gently as if he were handling butterfly wings, Nico lifted her tiny frame from the bottom, slid her inside the bag’s opening, and zipped it close. When he was finished, he tugged the rope around his waist four times, ascending with her body cradled in his arms.

~ ~ ~

Now, at the bottom of Alsea Bay, Nico tried calling Misty again. After hearing nothing back, he began to worry that his window for finding her may have already closed.

“Your mommy and daddy are worried, Misty. Parents get scared when they can’t see you. Tell me where you are, sweetheart,” he said pleadingly. “So, they can see you and know you’re okay.’

But Nico knew that when he found Misty Leander, she’d likely be unrecognizable to her parents even in the short time she’d been in the bay. Water was not kind to the human body, turning it into a soapy, amorphous version of its former self. Once the sea took a human body, an immediate macabre feast began, triggered by the onset of the body’s digestive acids. Putrefaction starts with the end of the body’s perfusion, the last heartbeat. This was the invitation to surrounding life, both visible and microscopic, to feast. Nibbling fishes and plucking crabs would seize first on the soft, exposed tissues of the face, eating away lips and noses to reveal the skull’s superstructure beneath.

The thought of the damage swarms of relentless, eight-legged, bottom-feeding Dungeness had likely already done to the seven-year-old made him shudder. When he did bring her home, he’d open the bag only enough to show them her pink sweatshirt. In past recoveries, he saw what happened when families insisted the black bags be fully opened. The horror was immediate and indelible. It is better to remember loved ones when they have faces, words, and breath.

“Misty,” Nico called out again, hoping if he couldn’t hear her, maybe he’d be able to pick up her thermal trail. This had been the other “gift” his almost-fatal meningitis had bestowed on him.

He encountered the phenomenon during the body recovery of a 12-year-old boy with Down’s syndrome who drowned in the Umpqua River when his mother had left him unsupervised for only a few minutes to use the bathroom of their rented holiday cabin. The boy had slipped from a steep bank and disappeared in a deep, narrow river stretch with a fast current. Reasonably, other search and rescue team members believed they would find the boy miles downstream, and that’s where they headed. Nico insisted on going in at the bank where the boy was last seen, even followed the sliding dirt trail of his sneakers to where they ended at the lip of the river.

Once submerged, he discovered what he could only describe as the boy’s essence, a slow-dimming warmth he could perceive even through the layers of his drysuit, mask, and gloves. He followed its path directly to the body, snagged on a submerged branch inside a calm eddy just 100 yards away. When he tried to explain this to his supervising officer, he laughed him off. Told him dead bodies didn’t leave heat trails. He had a harder time when Nico returned with the second one a few weeks later, then the third. Finally, he stopped asking how he did it, satisfied enough with the successful recoveries.

All that was fine with Nico, too, since he wasn’t sure how he did it. He just regretted not being ‘gifted’ with these abilities earlier. Maybe he could’ve used them to find the body of his father. He’d swam that same shoreline in Tarpon Springs for years after his disappearance but never once felt the trail of Georgios Papadopoulos. Never once heard his voice. Though he’d called to him so many times, he nearly drowned himself.

~ ~ ~

In the present, Nico thought about the song Timothy Leander said was Misty’s favorite and began humming it based on what he’d heard while playing it on his smartphone. He also looked at the console holding his submersible pressure gauge, indicating how much air he had left in his tank. He started with a total of 3000. PSI, but after 45 minutes of deep breathing in the cold water, it drained to 700 PSI. The typically conservative search protocols dictated he should end the dive at 500 PSI and swap out for another tank – or end the search for the day. He wasn’t ready to do either.

Nico stopped his finning and humming when he thought he’d heard something. Turn his right ear slightly in the direction of the sound. He expected to pick up on the echolocation that he could only detect in that one. Instead heard . . . the rollicking sound of piano keys? He shook his head, trying to clear the apparent malfunction, anything from a surface radio song caught and amplified underwater to an auditory hallucination. But after a moment of stillness, he heard it again. This time, it came with words: I've got my eyes on you, So best beware where you roam.

I've got my eyes on you, So don't stray too far from home.

Nico recognized and dismissed it immediately. It was from The Philadelphia Story soundtrack, Cole Porter’s I’ve Got My Eye On You. He rebuked himself as he so often did after his weekends of heavy drinking, a habit he’d yet to break even after being put back on the dive roster.

These were the side effects of passing out drunk in front of the tube so frequently it was able to paste its images and sounds deeply into his pickled brain. He refocused himself, but the song continued. He found it growing louder as he finned forward. The auditory montage became more layered as he chased it, peppered with lines from the film. With each turn he made toward the sound, they became clearer, more insistent.

Doggonne it, C. K. Dexter Haven, either I'm gonna sock you or you're gonna sock me!

Splendid chap, George. Very high morals. Very broad shoulders.

It - it can't be anything like love, can it?

No, it mustn't be! It can't be!

Would it be inconvenient?

Terribly!

From the shoreline, “I don’t know what’s up with this guy,” Johnny Bravo said, letting out slack on the rope tied to Nico’s waist. “But he’s gotta be close to zip on air . . . and it feels…” he looked at the twist in the rope, “like he just started swimming in circles.”

“Maybe he’s got something,” Ray Falk said, concealing his concerns. “Stay sharp.”

Nico kicked hard and pushed himself forward, Porter’s piano keys growing more frantic in his ear.

I've set my spies on you; I'm checking all you do. From A to Zee. So, darling, just be wise, Keep your eyes on me.

Thought he could see in the distance, a patch of pink, beautifully incongruous on the muddy bay bottom, pushed toward it, felt like he was kicking against the tide though he was with it, music swirling, swaddling, all his senses in a sumptuous moonlight fog.

There. So close. He reached, stretched, and strained until he felt something unravel.

Back on shore, the radio crackled, “Got her. I’ve got her,” Nico’s voice came through the static.

Ray Falk hurriedly picked up the hand mic on the box console. “Nic? You found her? Confirm.” A minute went by, then two. “Nic, confirm, please.”

Nico’s voice again over the radio, softer. “It’s okay, Dad. I’ll take her now.”

Johnny Bravo looked at the box, then at Falk, spun a finger around his ear, but then the tugs came so fast and hard that he nearly dropped the line.

“That was five … I think,” he said to Falk.

Falk nodded, “Pull him in.”

Seeing the commotion, the Leanders both rushed to the water’s edge.

But when the black bag reached the surface, Nico wasn’t with it.

“He’s probably just scouring the bottom for anything that might’ve been left behind,” Falk explained to the Leanders, but not entirely convinced himself. Then added, “That’s just the training.”

When Johnny Bravo tried to retrieve the bag, he found it too heavy to move. He and Falk grabbed opposite ends and, with difficulty, duck-walked it up the incline, setting it down in front of the Incident Command Tent.

“Open it,” Marian Leander demanded, kneeling beside the black, lumpy rectangle.

“Ma’am, you’re not going to want to see …” Falk said, holding out a hand, but before he could stop her, she unzipped the body bag and pulled back the entire length of the flap. She and the others reared back momentarily when a couple of fish flopped onto the sand, and a handful of crabs climbed off the mound inside.

A thick silence fell, and they all gathered and struggled to process what they saw. There before them, still in all his scuba gear, was Nico Papadopoulos, his arms and body protectively wrapped around a tiny inert figure dressed in a hooded, pink sweatshirt, pajama pants, and rain boots.

Timothy Leander knelt next to his wife. He reached for her hand and then used his other to lower Misty’s hood. The skin of her face was waxen and bloodless, drained of all color and life, but also wholly untouched—as if something had stood guard over her on the bottom, shooing away anything that might mar it. Both Marian and Timothy Leander nearly cried out her name in unison and pulled her out of the diver’s arms and into their own.

It took him a moment, but Ray Falk shifted his attention from the spectacle of the unmolested corpse of Misty Leander to the man who recovered it. He quickly removed Nico’s face mask and used EMT scissors to shear off his neoprene hood and latex neck seal. Falk bent down and put his ear to Nico’s lips while Johnny Bravo palpated his wrist for a pulse after stripping off one of Nico’s gloves.

Ray Falk shook his head. The younger man confirmed the same, then reached down to check the pressure gauge on Nico’s tank. Held it up for Falk to see. The needle was buried in the red. Not enough air left even to purge the regulator when Johnny Bravo gave it a squeeze.

-END-

[Note: A special thanks to Mike Berry, the godfather of police search and recovery diving and the author of The Water's Edge: A Manual for the Underwater Criminal Investigator. The book, along with his course, Public Safety Divers/Underwater Criminal Investigators, was used for reference in this work of FICTION.]

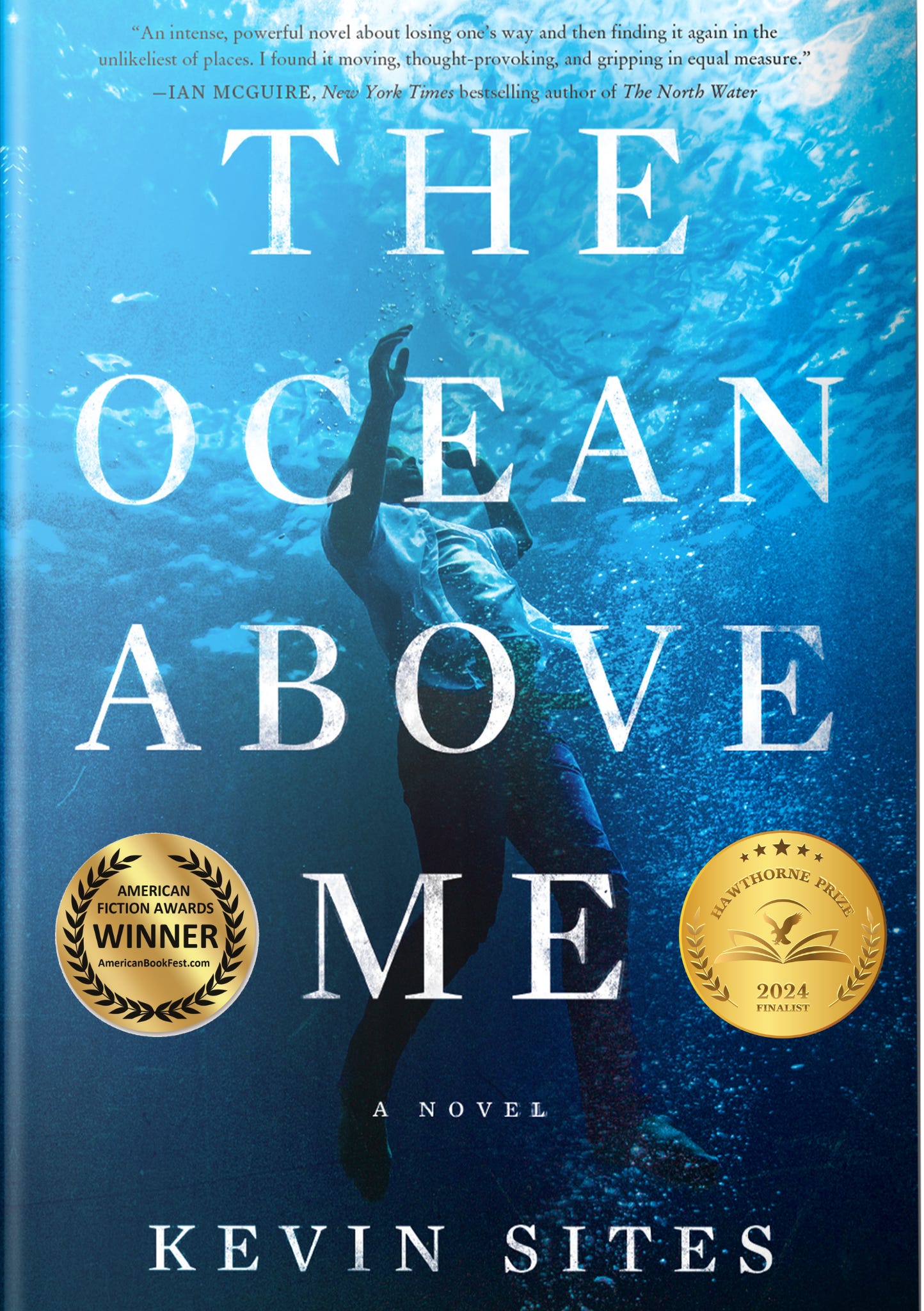

If you liked what you just read and want more, order Kevin Sites’s award-winning debut novel, The Ocean Above Me, available at the link below.

https://www.amazon.com/Ocean-Above-Me-Novel/dp/0063278286